Former Player Aaron Merz Dedicates Life After Football to International Aid

Many players form foundations during and after their playing days as a way to make a positive impact on their hometowns or team cities. But a life-long passion for helping others led former offensive lineman Aaron Merz halfway around the world after his playing days concluded. He and his wife, Leandra, began IIM International with the mission of helping youth in Zambia have two things that most Americans take for granted: clean water and a high school education.

By: Rob Troiano, NFLPA Communications

Images provided by Aaron & Leandra Merz, IIM International and Cal Athletics

Aaron Merz rises at 5:30 a.m. most mornings, but his day’s work is a far cry from the years he spent playing on the Buffalo Bills’ offensive line. The days of blocking sleds, film sessions and fighting to earn a spot on the roster have come and gone. Today’s challenges are bigger, and the potential impact of his work is immeasurable.

Aaron walks the 10 minutes from his home in Chalata, Zambia to a construction site, where he unlocks the storage facility that houses his crew’s tools and cement. His day will center around water. In fact, Merz said, “It seems like my whole life centers around water.”

He helps with odd jobs around the site but spends much of the day rolling 50-gallon drums of water up and down a hill that runs the length of four football fields to the nearest river. He says he never realized just how much water went into a construction project.

“Rolling a 50-gallon drum up a hill for 400 yards is so much harder than driving a sled ever was in football camp,” Aaron joked. “But I’m not a brick layer or a carpenter, and even if I had the balance to be up on the roof, at my weight, it’s not a good idea.”

After two seasons, Aaron walked away from the game, and his days as an NFL player came to an end. He doesn’t dwell on the past or consider what might have been. He says he has found his true calling in life, a cause he feels so passionate about that he has given up everything to pursue it. Aaron and his wife moved to the African nation of Zambia to build a foundation from the ground up.

IIM International gives orphans and at-risk children the chance at a hopeful future. Its potential is already being realized, as some individuals have already benefitted from its mission. Aaron and Leandra Merz’s focus, though, is not on who they have already saved – it’s the thousands more that still need saving.

***

Aaron Merz has always had an innate inclination to help others. It is a quality, he said, that was rooted in his upbringing. He and his three sisters were taught the benefits of working hard for what you want, while making yourself and your possessions available to those in need.

“There were never any extreme examples of us going on mission trips, volunteering at the soup kitchen or other clichés,” Aaron said, reflecting on his childhood. “I grew up seeing my parents spring into action whenever someone in our community, our church family, or a co-worker needed help. I guess I’ve just always known that as the only way to carry myself.”

Faith and football were two defining elements of Aaron’s upbringing. He was raised in a Christian household, and his family never missed church on Sunday. They prayed together before every meal and often had devotions in the morning before school. Although Aaron says his religion became a bit less structured as his life went on, faith has always been his most important influence.

Football, although something he always enjoyed, never achieved the same distinct importance in Aaron’s life. He starred at Wasco High School in Wasco, California and loved the game, but his mind harbored deeper ambitions. Merz saw himself as a well-rounded individual, and he says his primary goal in life has always been constant self-improvement and exploration.

Though Aaron pushed back against being labeled as a jock, when the football season ended, he immediately looked ahead to basketball in the winter then golf in the spring. He lettered in all three sports and won All-League honors as both an offensive and a defensive lineman. Yet the opportunity to pursue a future in the game caught Aaron off guard.

***

In eighth grade, Aaron read that the University of California, Berkeley boasted the top engineering school in the country. He immediately shared with his mother that his goal was to attend California and study engineering. Little did he know at the time, his football success would allow this dream to become a reality. Cal happened to be the only NCAA Division-I school that recruited Aaron. It was a fortunate turn of events, but his luck ended there. The school had no additional scholarships to offer. Aaron could join the team, but he would have to begin his collegiate career as a recruited walk-on and earn a scholarship.

Not one to be deterred, Aaron met this resistance head on and embraced the opportunity to prove himself. After a redshirt year, Aaron saw the field occasionally in 2001, sufficiently impressing his coaches as he entered the next season as the top backup to the starting left guard. An injury-prone upperclassman, the starter missed the majority of games and Aaron had the chance to start eight games out of 14. It was the opportunity he had been waiting for. Shortly after the season, he was notified that he would be awarded a scholarship for the 2003 season.

“I remember feeling a huge sense of justification,” Aaron said. “I felt like I had been cheated to a certain degree, as dozens of scholarship players rode the bench. At the same time, I was also enjoying myself because I was already getting a reward for my hard work by being able to actually play in the games.”

Aaron said that above all, he cherished the moment he shared the news with his parents. After all they had done for him, he was proud to no longer be dependent upon them or student loans.

“I know that they would have continued to support me through college,” he said. “But to be able to secure that scholarship and let them only worry about my three sisters felt good.”

Despite his scholarship and starting position, Aaron remained focused on what he would do after graduation, when football would be behind him. Then, when watching the 2004 NFL Draft, he saw teams claim linemen he had played against, linemen he knew he could beat. At that moment, the idea he could play in the NFL took root, even if the uncertainty of making it his life’s work lingered.

***

Aaron, feeling the pressure to make the most of his physical gifts, dedicated his senior year to football.

“Everything I did was about promoting the image that I was dedicated to football and only football,” Aaron said, “The NFL had shown it wasn’t interested in athletes who have other interests or abilities.”

Merz took a single two-unit class for his sociology senior seminar, and says that outside of that class, he lived and breathed football. Constant workouts, practices and film sessions prepared him for a season that would put him on the radar of NFL teams. His hard work paid off. Other than a serious concussion he suffered in September, it was a successful season for Merz individually.

When he scored a 39 on the Wonderlic test, a test given to all college players entering the draft, his agent was not necessarily pleased. Merz was told a high score could reflect poorly on an offensive lineman, as scouts believe it typically indicates a level of indifference towards football. According to Sports Illustrated’s MMQB, most linemen score in the low 20s.

Scouts indeed questioned him about his score, forcing Aaron to admit that although he was currently dedicated to reaching the NFL, he was confident he would be perfectly fine pursuing other ambitions. The answer may have scared off some teams on draft day, but in the seventh round, Aaron achieved yet another goal.

With the 258th pick in the 2005 NFL Draft, the Buffalo Bills made Aaron Merz an NFL player.

***

As a rookie, Aaron appeared in seven games, starting one. He then spent his entire second season in Buffalo on the Injured Reserve list after suffering a shoulder injury during training camp. He had already struggled through multiple operations on the same shoulder in college and resigned himself to another season of rehabilitation.

During the first game of the 2007 NFL season, Bills tight end Kevin Everett suffered a career-ending neck injury that left him with very little hope of ever walking again.

“I had already been having strong feelings about moving on from the game and using my body and gifts for different purposes,” Aaron said. “But watching what Kevin went through seemed to make things even more clear.”

While concern over his long-term health lingered, another door opened for Aaron that would set the stage for his life after football.

With the spare time his IR designation provided him, Aaron began working with a small community of Somalian refugees who had been relocated to Buffalo. A local Presbyterian church was helping the refugees, but the children had been placed in the public school system and were essentially left to fend for themselves.

“The church recognized that many of these children were struggling to adapt to their new culture and schools,” Aaron said. “[They] were trying to offer a one-on-one environment where the students and a tutor could go through coursework but also talk about their daily struggles with adapting to American life.”

Aaron had been dreaming of doing mission work since he was young, and his experiences at the Presbyterian church reignited this fire. At this point, he had nothing left to consider. When the football season ended and Aaron was released from his contract with the Bills, he had already started the application process for the Peace Corps.

“By the time I was ‘medically cleared’ and the Bills could legally release me from my contract, I was already mentally preparing for the next phase in my life,” he said.

On the Peace Corps application, Aaron listed sub-Saharan Africa as the region to which he most wanted to be assigned.

***

Aaron stopped reaching out to NFL teams and declined all tryout offers. In February of 2009, he began his service with the Peace Corps and was sent to Zambia. Aaron believed he was finally on the path he was called to be on. He was truly happy with the work he was doing, and made plans for a productive two-year stay in Zambia.

Unfortunately, life doesn’t always go according to plan.

“In November of 2009, I reported to the medical staff that I had been suffering from headaches, vertigo and some vision problems,” Aaron explained. “Over the next five weeks, they exhausted the tests that could be performed in Zambia and decided I needed to be sent back to the United States for further examinations.”

The setback crushed Aaron. Not only was he being pulled away from his work, he was facing a mysterious and debilitating illness. Walking just a few blocks left him weak and dizzy, and there was no diagnosis or prognosis.

Peace Corps protocol prevented Aaron from returning to retrieve his belongings or bid farewell to the family that had taken him in. The village was in the midst of planting season, and Merz was the caretaker of three tree nurseries. Without the opportunity to let his Zambian family know what was happening, he felt as though he was abandoning them.

“Peace Corps decided to send me home. When they make that decision, for whatever stupid, bureaucratic reasons, it happens with finality,” Aaron said. “I felt as if I had been wasting the last six weeks while being held in the facility in Lusaka, yet I couldn’t get a day to go back to my village and gather my things and say goodbye to my family. I was put on the first flight out the next day.”

As he boarded the plane home, he promised himself he would return one day to explain why he had left.

***

Doctors in the United States believed his illness had been brought on by stress and rapid weight loss (Aaron had lost nearly 100 pounds in 9 months), and prescribed him rest. But his symptoms only worsened, and finally an MRI revealed a large tumor on the fourth ventricle of his brain. The mass was blocking the release of cerebrospinal fluid and placing pressure on his spinal cord.

“I was actually more relieved than anything else to get this diagnosis,” Aaron said. “Anyone who’s been sick for a long time with no answers can tell you that another negative test is the most frustrating result to receive.”

Aaron underwent two surgeries near his home in California, and a shunt was placed in his brain to help his body regulate the spinal fluid. He spent months in recovery, and his reliance on his family left him dejected.

“My village life in Zambia was one of the happiest, most fulfilling experience I had ever known. I was taken out of it and thrown into a situation where I couldn’t do much for myself,” Aaron explained. “I was no longer working towards helping a community become food secure but rather was reliant on my parents or my sister to do a lot of my daily tasks.”

The difficulties of brain rehabilitation proved especially challenging. The results are not often tangible, and it was difficult for Aaron to know how much pain was appropriate, and when he needed to pull back on rehabilitation. He suffered severe memory loss initially, and turned to carrying a notebook to record his thoughts.

Aaron still takes a small pile of pills every day to regulate his headaches and prevent seizures. He still suffers from memory loss at times.

“I’m not the guy who scored a 39 on the Wonderlic, and I know that I could never do that again in a dozen tries,” he said. “I now have a new baseline for pain, balance and comfort and when I’m unable to achieve that baseline, I seek help. I have to live with it, and be thankful that I am living with it.”

***

Before his initial Peace Corps trip, Aaron went through training with a young woman named Leandra Clough, from West Palm Beach, Florida. Leandra had been a part of the same Zambia intake as Aaron, and their posts were only 70 miles apart, so they crossed paths from time to time during service. Their limited interactions hadn’t resulted in any hints of romance, and when Aaron was eventually recalled, Leandra filled his position in his village.

Rehabilitation behind him, Aaron spent his days working with his family’s almond business in California. He was restless, but the time spent regaining his physical strength proved essential. When harvesting season came to an end, Aaron began preparations for a trip back to Zambia.

“I put a message on Facebook saying that as soon as we were done harvesting, I wanted to go back to Zambia for three or four weeks,” he recalled. “I was planning on renting a car and wanted a travel buddy to help pay for fuel. Of all my friends, Leandra responded saying that she had similar goals. She felt like she had unfinished business in Zambia.”

Leandra, too, had been sent home early from her Peace Corps service for medical reasons.

The two departed for Zambia in November of 2011, where they reunited with old friends, visited familiar villages and participated in a range of humanitarian projects. The two bonded over their unique yet similar circumstances and desires.

“[Our friends] were shocked that we were traveling together because apparently Leandra and I had not been very friendly to each other during our service,” Aaron recalled, laughing. “I remember joking at the time that by the end of our four weeks, we were either going to be dating, or one of us would have killed the other.”

The two delivered bags of donated clothing and prepared meals for the Basic School in Aaron’s old village. They bonded over the adversity they had faced in leaving Zambia, and developed a powerful connection along the way.

“It was an intense trip emotionally,” Aaron said. “We bonded over a lot of shared experiences.”

Aaron reconnected with his host family and was relieved to discover they harbored no anger over his disappearance. He finally had a chance to explain, lifting a weight of regret off his shoulders. It was a catharsis, and Aaron was finally walking the path he had always imagined for himself.

***

One of their last stops was to Leandra’s first village, where she had been stationed prior to her reassignment. Leandra had worked closely with a number of students and had become especially close with a sixteen year old orphaned boy named Mayben. Through conversations with old friends, Leandra came to realize an unfortunate but all too common truth of the region. Although many of her students, including Mayben, had earned high marks on Zambian national qualifying exams, the majority lacked the funds to pursue secondary education.

In Zambia, primary education is free, but further schooling is expensive. Parents typically struggle to send even one child to secondary school - orphans and the extremely poor have no hope of continuing their education without assistance. The vast majority of orphans spend their years after the eighth grade working on a farm to support themselves. There are no night classes or online courses – they must work to support themselves at the age most Americans would be starting high school.

Mayben had been plagued by tragedy throughout his young life. An orphan and the only surviving child of three siblings, he had been taken in by his uncle Ackson, a prominent farmer in the area and Leandra’s primary counterpart during her initial term of service. Although Ackson was able to care for Mayben, he was not in a position to fund his schooling, and Mayben was set to be one of the many bright and inquisitive students whose education ended at eighth grade.

Leandra, heartbroken by this sad truth, decided that she was in a position to help. After some deliberation, she offered to sponsor young Mayben’s secondary education.

She began looking into secondary schools in the area, familiarizing herself with the fees and processes necessary to facilitate a student’s secondary education from America. Ackson stepped up as the intermediary between Leandra and the Chalata Secondary School. He ensured that the fees Leandra sent would be given to the school as Mayben’s tuition.

“What started with Mayben, Ackson recognized as a bigger problem,” Aaron explained. “He presented Leandra with nine other students from the village who were orphans and were accepted into Chalata Secondary School but had no means of paying the fees.”

This was the moment of no return for Leandra – she lacked the personal resources to sponsor all of the students, but a commitment on whether to help the others had to be made. Accepting the responsibility carried a heavy burden, and she took her time with the decision.

***

Imiti Ikula e Mpanga is a Bemba proverb best translated to mean “small trees grow to become a forest.” After days of prayer and consideration, Leandra decided to take it a step further than simply accepting the challenge of sponsoring the children. She formed a non-profit, registered in her home state of Florida as Imiti Ikula e Mpanga. She knew the impact her foundation had could be boundless – who knew what these children could grow to become if given the opportunity?

The first official IIM International event was a dinner, hosted by Leandra and her mother in June 2012 at the Palm Beach Zoo where Leandra worked. The goal was to match the children that Ackson had presented with donors who would put them through school. Ackson provided a photograph and application form for each student, and Leandra prepared basic bios to present to her dinner guests.

Mayben’s story was presented first, and was used as a case to explain in-depth the situation of the youth in the region. It is common practice in Africa for extended families to take in orphans, but the HIV/AIDS crisis in the region can lead to more orphans than there are families with the ability to care for another child.

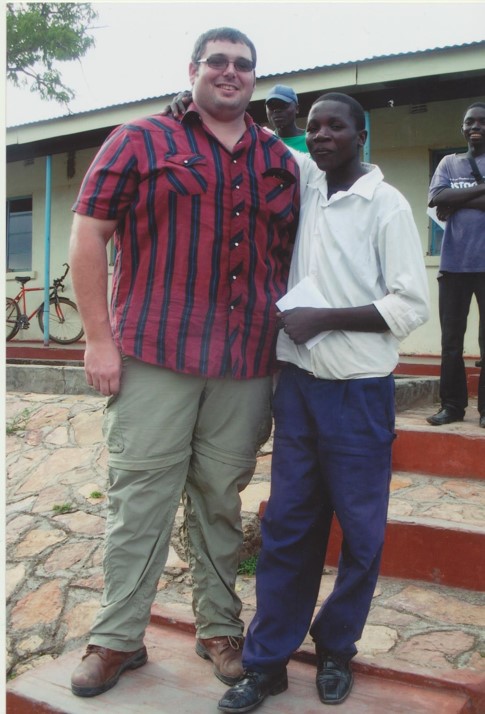

Leandra presented to the group that like every American boy or girl his age, Mayben is full of ambitions. He is passionate about football (soccer) and enjoys running track. His favorite event is the 5,000 meters. Mayben lists geography and accounting as his favorite subjects and hopes to attend college and eventually become a teacher. Without a secondary education, however, these dreams would be unrealized.

That first dinner in 2012 was IIM International’s first attempt to end the cycle - the evening ended with a sponsor for each of the students. With one dinner, the courses of 10 young lives were forever altered, and Leandra and Aaron were hooked.

***

Starting a successful foundation is a constant learning process, one of trial and error. Leandra and Aaron had no prior experience, and they were building IIM International from the ground up.

“Initially, we just wanted to get these kids into school,” Aaron explained. “If we were able to give them the opportunity to go to school, they could then have the choice of whether to make the most of the opportunity or not. As are most things in life, it turned out to not be so black or white.”

Aaron went on to explain where the gray area exists.

Aaron and Leandra initially failed to grasp the extent of the damage that a lifetime lacking in structure and social support had on the students. Many had undergone traumatizing experiences in their lives, losing parents and siblings while struggling with poverty. Signing orphans up for school and paying their tuition was not going to solve the larger problems.

“It opened our eyes up even more to the great effort that our own parents put in to enhancing our educations. They asked us about homework every night, drove us to various afterschool events, made sure that we had every supply for every subject, and a million other things that I always took for granted,” Aaron said. “These kids don’t have that, and to expect a 16-19 year old to do any of that on his or her own without an example is impossible.”

Sponsoring the student’s education was certainly making a difference, but providing additional structure and support was a logical and, they were learning, necessary next step.

In early 2012, Leandra was working as a keeper for the Palm Beach Zoo, and Aaron had moved back to California. He spent nine months between the end of 2012 and 2013 in Kenya and Zambia, volunteering with Jubilee Farms to train farmers in sustainable farming methods and land management. He journeyed to Chalata regularly to check in on the sponsored students and handle administrative details. Aaron was establishing contacts across the world while Leandra was working domestically to get IIM International off the ground.

Despite the distance, the relationship between Aaron and Leandra had blossomed, and with it Aaron’s commitment to IIM International.

“She asked if I was interested in being on the board of directors,” Aaron said. “Throughout 2012, I was only an advisor, so to speak, and neither of us had the vision that we would be dedicating ourselves to full time management of the organization.”

He had promised to “win her heart” shortly after their return from Zambia. “I don’t know that she took that statement very seriously, but obviously I meant it,” he said.

Their connection had survived the long distance, and in May of 2013, Aaron and Leandra were engaged. At the time, Aaron was still in California, helping his family with their almond crops, and Leandra was completing her Master’s degree in Sustainable Development at the University of Florida.

Aaron was brought on to the Board of Directors for IIM International by late 2013, and the two began discussing the future of the organization.

“We realized during that period that IIM needed more hands-on management,” Aaron explained. “When we developed the idea of building a dormitory and a center for everything. We made the decision that we had to be here to oversee the construction and to train the staff that such a center will require.”

Their marriage in December of 2013 coincided with their decision to move to Zambia full time, with plans to build a dormitory and a student center for their students.

The two remained together in Florida until Leandra was able to complete her degree. By May of 2014, they were living in Zambia, their lives dedicated to building IIM International into an organization that could make a tangible, lasting difference.

***

The simple pleasure of running water is rare in Zambia. Aaron and Leandra had lived life in spurts without these basic pleasures, but a return to America and its comforts was always in sight. A permanent life in Zambia required them to embrace the inconveniences.

“The biggest thing about life here is that you earn literally everything you get. This morning, I waited 45 minutes as my two 20-liter cans of water were slowly filled by the tap at our compound. But it’s worth it, because the tap is only 50 yards away from our back door, and the source is ground water which is much cleaner than water from a stream,” Aaron said. “The alternative would be to walk half a mile to the river where I could fill up the cans really quickly, but then I’d have to carry them all the way back. So I wait for the cans to fill, then carry them the 50 yards up the hill to our house and put a liter at a time into an electric kettle to boil so we can start filtering our drinking water.”

All of that physical labor and time, just for a kettle of clean drinking water. Leandra uses another of the cans to hand wash their clothes, and the two use a bucket of water and a cup to bathe. This is life, every day, for the Merz family. Still, this is the life they chose, and they embrace it without complaints.

***

After two months of preparation, ground broke on the IIM International Student Life Center in August 2014. The basic dormitory holds beds with mosquito nets, and students will also have access to three nutritious meals a day and clean drinking water. By housing the students together, Leandra, Aaron, the other staff members and the “house mother” can more easily provide a structured setting and attend to the social needs of their students.

The original 10 students from Leandra’s dinner, plus two additional ones, will start school on IIM International scholarships in January.

“When you talk about goals for IIM International, you’re talking about things that we expect to obtain through our hard work,” he explained. “Those goals evolve as we grow. Within the scope of what we’ve already developed and financially committed, we want to expand from 12 students this year to 24 in 2015. To do that, we need to identify students who meet our criteria and get sponsors to sign up for each child. We also need our existing sponsors to continue their commitments for another year.”

The hope is that the SLC will serve not only as a self-sustaining home for students but also as a community and learning center for the village. The plot is large enough for IIM to develop a small orchard and keep small animals such as chickens, pigs and rabbits.

“Gardening will be a big part of our facility’s sustainability,” Aaron said. “Between the orchards, proteins, and vegetable gardens, our goal is to be completely self-sustaining in terms of feeding our students within five years. Ideally, we will even be able to sell excess eggs and pork to the local community to help cover other overhead.”

***

Two intermediary projects must be accomplished first: Providing reliable, clean water to the SLC, and installing a bio-digester toilet system that will allow for the harvesting of methane gas for cooking fuel.

Fortunately, positive steps have been made. Aaron and Leandra have raised enough money to buy a water pump and have contracted a company to drill a well. It is a short-term solution, but one that will suffice until additional plans can be made. To ensure students remain focused on their studies, and perhaps more importantly, enjoy their youth, IIM is looking for a permanent solution so the children will never have to worry about carrying buckets on long hikes to and from a water source.

They hope to secure additional funding to apply a solar-powered pump, a water tower with capacity for 10,000 liters and plumbing for the various buildings on the site.

With the bio-digester system on hold, latrines were dug so that facilities would be available when the center opens in January. The holes are built for the assembly of the bio-digester toilets, but as Merz said, “labor is cheap, engineers are not.”

Just before Christmas, Aaron and Leandra reported a major victory. Thanks to a couple of major donors (including a former NFL player), a mono pump borehole was installed on the property. The pump will guarantee that clean drinking water is available 24 hours a day while they continue raising funds for the solar-powered pump and tank.

***

Aaron spends his days managing the Student Life Center’s two separate construction sites. He’s not a bricklayer, not a carpenter, but he does all he can to help. Most days, it’s rolling those 50-gallon drums 400 yards up the hill and 400 yards back. They go through anywhere from six to 10 a day.

Each drum brings Aaron and Leandra one step closer to making IIM International a resource for an entire community. Securing a new sponsor for a child’s secondary education does the same. Neither are easy work.

“We regularly visit the primary schools that feed the secondary school where most of our kids attend,” Aaron explained. “The Headmaster will give us a list of dozens of kids who are in 8th or 9th grade who are excelling in their classes but are also being monitored by the Ministry of Social Welfare because of their status as Orphans or Vulnerable Children.”

Choosing children from the seemingly endless list is certainly an unenviable task. But every donation means progress, moving one student at a time off that list and into IIM’s program. Their goal of expanding to more than 20 students is within reach.

A full year of secondary school in Zambia costs just $400.00, or $35.00 per month via a recurring payment plan. Aaron and Leandra also welcome donations to their general fund, which will go towards the construction of the water pumps and other essential projects at the Student Life Center.

“I believe we’re on the cusp of dramatically impacting a whole community, and eventually a nation,” Aaron said.

To donate and learn more, please visit www.IIMInternational.com. You can Like IIM International on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/IIMinternational and follow them on Twitter at @IIMInter.