The Five Players' Associations Thank Senator Bobby Joe Champion

May 16, 2016

Senator Bobby Joe Champion

3207 Minnesota Senate Office Building St. Paul, Minnesota 55155

Dear Senator Champion:

On behalf of the members of five of the leading professional sports players’ associations in America: the Major League Baseball Players Association, the National Basketball Players Association, the National Football League Players Association, the National Hockey League Players’ Association, and the Major League Soccer Players Union - we want to thank you for your efforts to clarify the right of publicity in Minnesota. We support the objective of SF 3609, the PRINCE Act – to protect the ability of Minnesotans to have some control over the use of their name, voice, signature and likeness for commercial profit, without their permission. Unfortunately, the current draft of the legislation, with all the commercial exemptions it provides, may end up swallowing the very right the bill wants to create. Specifically, the exemption for “other audiovisual works” is being used to try to abrogate existing protections that athletes, musicians and other celebrities currently have.

Today, in Minnesota and around the country, when alleged free speech interests collide with other protected interests – like the state law right of publicity – the courts require a balancing test and it’s the job of the courts to strike the legally required balance, based on the unique facts presented. This happens in other First Amendment cases. Take, for example, a lawsuit involving libel. The injured party files suit. The defendant says he or she has a First Amendment protection. The court then has to balance a person’s state law right not to be libeled with someone else’s First Amendment right to speak – whether that speech occurred on television, or in a movie, or on a poster, or in a video game.

The most current version of SF 3609 would eliminate this balancing test for an array of commercial interests. It would deny individual Minnesotans their day in court. Under current law, they may not win but at least they have an opportunity to make their case that their identity is being used by another, without permission, to make money.

For example, today, in Minnesota, if a concert promoter would like to stage a concert using the digitized likeness of a popular rock musician artist, it would need that artist’s permission. If the revised draft of the bill is enacted, it would not.

Similarly, if a multinational entertainment company wants to make a video game depicting Kevin Garnett playing basketball, Zach Parise playing hockey, a Minnesota Viking playing football, a Minnesota Twin playing baseball, or a Minnesota United FC member playing soccer, it would need their permission. If the revised bill is enacted, it would not. Today, gaming companies pay for the right to use the names, likenesses, mannerisms and voices of professional athletes, musicians and other celebrities in their video games. These same companies have argued in other states, when comparable legislation was being considered, that including the phrase “audiovisual works” in the list of exemptions will end their need to continue paying for this use. The bill being considered in Minnesota contemplates this very language--granting exceptions for other audiovisual work--that according to the video game makers would obviate their responsibility to seek consent from these celebrities for use of their likenesses and erase the first amendment protective rights of these celebrities as previously interpreted by the courts.

Reliance on a balancing test is well established in the courts. In the now famous human cannon ball case, Zacchini v. Scripps Howard Broadcasting Co., 433 U.S. 562 (1977), the Supreme Court of the United States was asked to address whether a television station broadcast of Mr. Zacchini’s 15 seconds-long human cannonball act on the evening news violated his right of publicity. The Court ruled that the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution did not provide the television station with blanket immunity to violate Mr. Zacchini’s right of publicity.

The court noted that the primary purpose of the right of publicity is to prevent unjust enrichment. Because Mr. Zacchini had expended time and energy to cultivate this skill, the value of which is derived from the entertainer’s exclusive control, the Court held that appropriating the act in full took away Mr. Zacchini’s opportunity to charge an admission fee and violated his right to protect his name and image.

In No Doubt v. Activision Publ’g, Inc., 192 Cal. App. 4th 1018 (Cal. App. 2011), the court rejected the video game manufacturer’s First Amendment argument. Similarly, in Keller v. Electronic Arts, Inc., 2010 WL 530108 (N.D. Cal., Feb. 6, 2010), a video game’s use of a former college athlete’s identity was held not to be protected by the First Amendment. Other recent cases holding that the right of publicity protects the unauthorized commercial exploitation of student athletes’ and professional athletes’ likenesses against First Amendment challenge include Hart v. Electronic Arts, Inc., 717 F.3d 141 (3d Cir. 2013), and Davis v. Electronic Arts, Inc., 775 F.3d 1172 (9th Cir. 2015), cert. denied, 136 S.Ct. 1448 (2016), in which the U.S. Supreme Court denied review just a few months ago.

The Supreme Court case of Brown v. E ntertainment Merchants Ass’n, 131 S. Ct. 2729 (2011), also did not support the kind of broad exemption found in the bill. The issue before the Court in Brown was whether the state of California could regulate the sale of video games to children if the games depicted killing, maiming, dismembering, or sexual assault. That decision does not stand for the proposition that all video games are completely protected by the First Amendment from otherwise applicable state laws, as some have argued.

This issue has been considered in other states and similar attempts to legislate exemptions to the right of publicity have failed in Michigan, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Maryland and Georgia, to name only a few. They understood that the real consequence of such exemptions was not to give individual citizens more control over how their names and identities are used but instead allowed them to be exploited for financial gain without their permission.

We appreciate your interest in this issue and the thoughtful consideration the Senate Judiciary Committee is giving this legislation. This is a subject that deserves serious discussion about all potential consequences to determine the best way to protect the publicity rights of Minnesotans.

We look forward to working with you to find an equitable solution and hope you will agree that the cost of codifying a state right of publicity law should not be that some Minnesotans will have less protection than they currently enjoy.

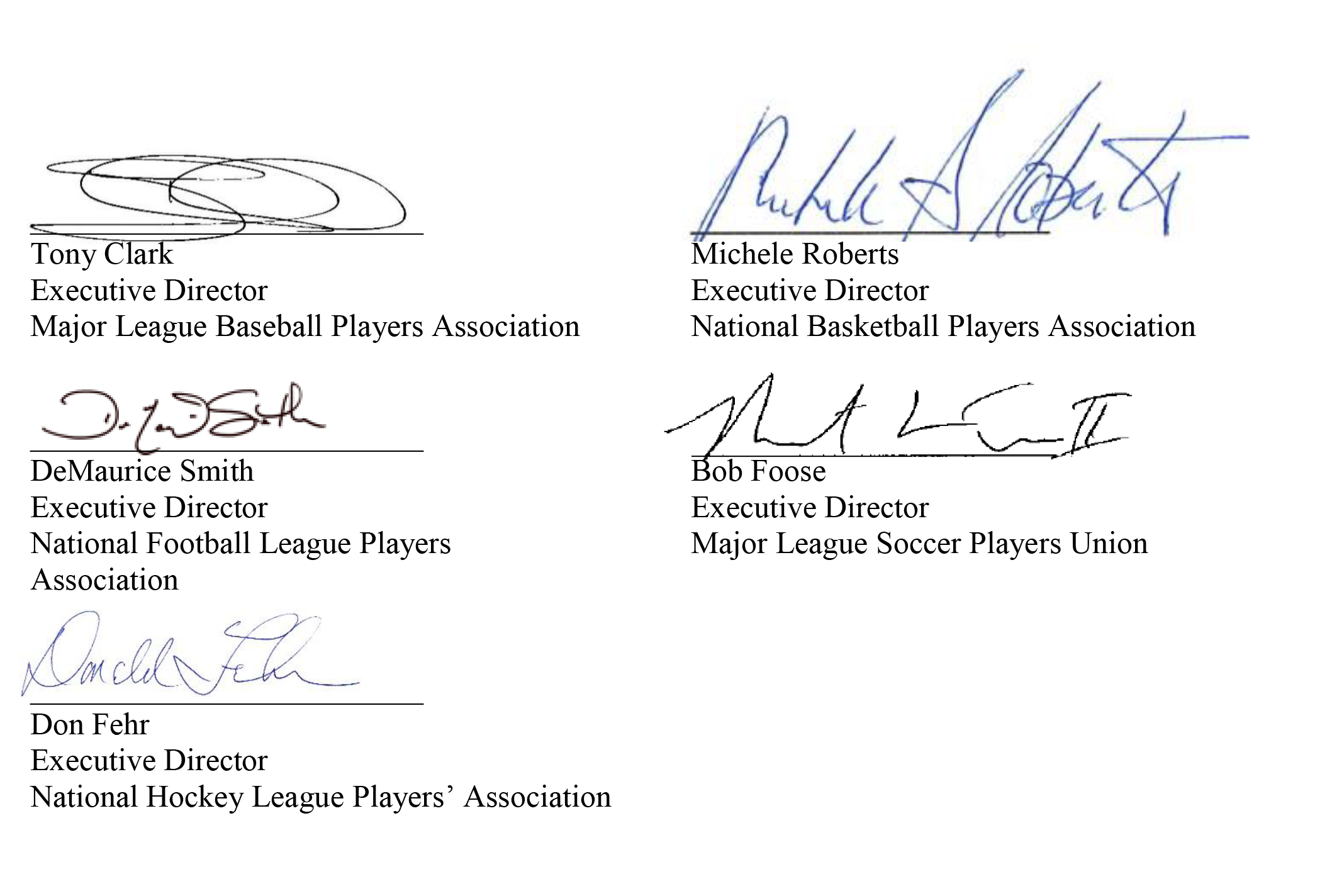

Sincerely,