The Irreplaceable Players of the 1987 Strike

The cherry red Porsche pulled into the parking lot, its engine humming along with the chants from thousands of union demonstrators lined outside Veterans Stadium.

On any other Sunday morning, the gleaming new car would have been all the talk among the Philadelphia Eagles as they prepared to host the Chicago Bears. But with the 1987 players’ strike in its 13th day and the Eagles joined by more than 4,000 union workers outside the stadium in protest of the replacement game being played that afternoon, that day’s purpose was to highlight what the NFL players did NOT have in terms of free agency and other rights.

“I told him as his teammate that I loved his car and was happy for him, but you’re killing the image we’re trying to project about unfair wages and player rights,” recalled a laughing John Spagnola, the Eagles Player Rep at the time. “He’s a great guy and rushed out of there and came back without the car to walk the picket line.”

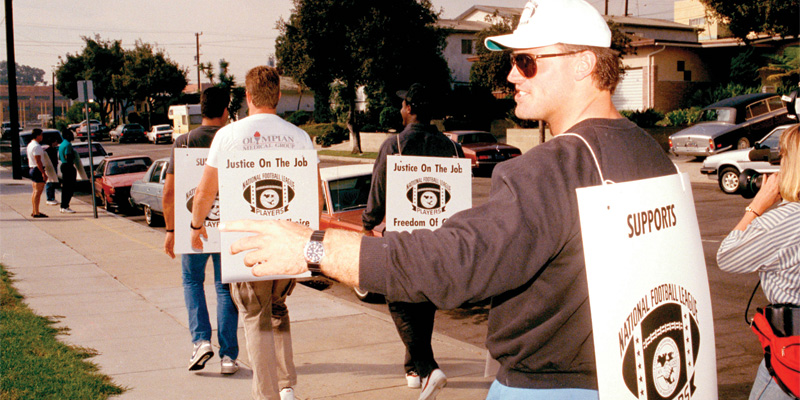

Joining them were supporting union members like the Teamsters and United Aerospace Workers Local 1069, all seething with passion for the players’ fight to maximize their earning potential through free agency. The rally served as one of several demonstrations during the 24-day strike, sending a message to owners and fans that the players were serious about their demands.

Other efforts across the league, orchestrated by Player Reps like Atlanta’s Mike Kenn and Washington’s Neal Olkewicz, included blocking the buses of replacement players from entering team facilities as well as some player wives and girlfriends holding bake sales to raise profits for one-way tickets out of town to offer the so-called scabs.

The strike began on September 22, and the strikers took their lumps along the way. Players lost an average of $15,000 per game. Owners sullied the records and integrity of the game by bringing in replacement players to take the field before TV cameras. And with no union strike fund to pull from, four weeks without a paycheck was a scary notion for the average player.

But while some high-profile names elected to cross the picket line, nearly 85 percent of the league’s 1,585 players stayed true to the union and its cause.

“We saw owners had free agency in a sense that they could pick up a franchise and abandon a city for another one if the money was better, but they wouldn’t let us as players do that,” Spagnola said. “I saw that dichotomy in the sport and without free agency, we were never going to get our fair share of the overall pie in the NFL.”

When the strike ended on October 15, the players still did not have any of their demands met, which is why, on paper, the owners could be declared the winners of this particular movement. But the work stoppage did create the momentum and determination necessary to endure the next six years.

After decertifying as a union in 1989, filing several lawsuits and going six seasons without a collective bargaining agreement, the players gained free agency and a guaranteed percentage of future gross revenues in 1993.

“The strike wasn’t a shining moment for the NFLPA, but in the long term, it helped us prove our case legally,” said former NFLPA general counsel Richard Berthelsen, who played a key role in the negotiations. “It showed how strongly players were behind the effort of free agency, which is something they eventually won.”